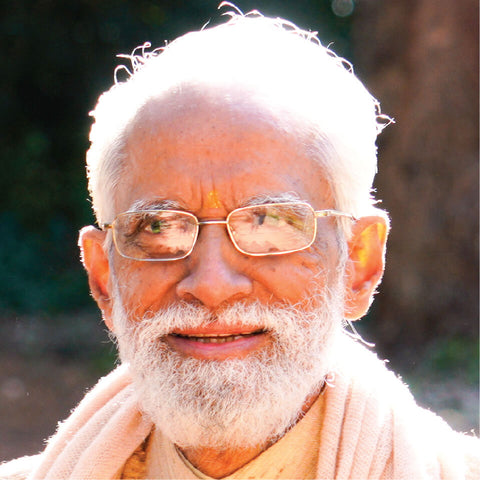

A. G. Mohan: An Incorrect approach to yoga practice

Share

The original article in Czech language by KORENYJOGY.CZ

This short sample is from the book "Yoga for Body, Breath and Mind" by A.G. Mohan, who is one of Sri T. Krishnamacharya's longtime disciples.

It is even the only book for which Krishnamacharya himself wrote the preface (in Sanskrit). For me personally, it was an extremely beneficial book in my asana (and pranayama) practice, and I can definitely recommend it - it is absolutely essential for those interested in yoga in the tradition of T. Krishnamacharya.

This is the last chapter, and a long time ago I translated the part about standing on the head because it was relevant. And here it is:

Any therapeutic practice worthy of the name has the power to effect significant change. Unfortunately, the very fact that these practices have so much power means that if used incorrectly, they can cause change that we don't want. In the case of yoga, the practice is all too often performed without sufficient knowledge or instructions, or with ambitions that can cause considerable problems for students.

Yoga is a slow, reflective process, the results of which come from the process itself. Practice done right automatically leads you to reflect on your experience. You will learn to read your own body, breath and mind. You will know and become aware of what to do, what to stop, what to change and when to do it, whether it is the practice of asana, pranayama or dhyana. Without this reflection, supported by appropriate technical information and guidance, the very foundation of the practice would be missing.

One of the most common misconceptions about yoga is practicing poses that look dramatic and impressive—such as headstands or candlesticks—but are completely inappropriate for the student. If you don't think about it, if you haven't received enough instruction, or if you're attached to the drama of the position, you won't know when you're hurting yourself.

A typical example of the wrong approach is the inappropriate practice of a position that we think will bring us some desired effect. For example: a young lad, a student, came to us and was generally in good health with one exception. He had numbness in his fingers that made it impossible for him to hold a pen and write. Upon investigation, we found out that he stands on his head every day - in his case for twenty minutes - because his grandfather told him it would help him do better on his exams at school. Further observation showed that his body was not in the right condition for this position and we advised him to abandon the headstand and instead engage in a practice that would prepare him for this position.

This case is not exceptional. There are a number of cases where improper headstand practice has led to problems such as loss of sensation in the arms, difficulty speaking, etc. Generally, these ailments are the result of positional dependence along with a lack of reflexes. Just as this young student followed his grandfather's advice, students often blindly follow instructions that may not be appropriate for the situation or body. Without self-evaluation and reflection during practice, they cannot connect the problem to its real cause.

A similar misunderstanding can also occur in the case of the practice of pranayama and meditation. Once a man came to us with neck problems. It turns out that he decided to follow the traditional breathing ratio that he found in a book: 1:4:2:1, in which he held his breath for 24 seconds. He chose this ratio based on the assumption that he was holding God within him for 24 seconds during each round of practice, or about 30 minutes a day.

It was obvious that he was straining his system by forcing himself to hold his breath for so long. We recommended a different ratio and his problem was solved. In this case, he inadvertently caused health complications by not having a teacher to observe him and his condition and by assuming that the ratio described in the book would work for everyone.

The student must also understand the real content of what he or she is doing in the practice of yoga. Once a woman came to us and complained that even though she meditated for three hours a day, she had no peace in her mind. It turns out that he uses meditation as an escape from his duties in a large family. True meditation should bring her a sense of calmness that allows her to look at things from a different perspective. Instead, she came out of meditation angry that she had to go back to her daily life again. Meditation is not an escape.

Finally, we would like to caution yoga students to be careful about self-teaching. Learning asana practice by yourself from books is unwise, not because the particular book you are using is lacking in something, but simply because no book can know the details of your condition.

Yoga is a slow, reflective process, the results of which come from the process itself. Practice done right automatically leads you to reflect on your experience. You will learn to read your own body, breath and mind. You will know and become aware of what to do, what to stop, what to change and when to do it, whether it is the practice of asana, pranayama or dhyana. Without this reflection, supported by appropriate technical information and guidance, the very foundation of the practice would be missing.

One of the most common misconceptions about yoga is practicing poses that look dramatic and impressive—such as headstands or candlesticks—but are completely inappropriate for the student. If you don't think about it, if you haven't received enough instruction, or if you're attached to the drama of the position, you won't know when you're hurting yourself.

A typical example of the wrong approach is the inappropriate practice of a position that we think will bring us some desired effect. For example: a young lad, a student, came to us and was generally in good health with one exception. He had numbness in his fingers that made it impossible for him to hold a pen and write. Upon investigation, we found out that he stands on his head every day - in his case for twenty minutes - because his grandfather told him it would help him do better on his exams at school. Further observation showed that his body was not in the right condition for this position and we advised him to abandon the headstand and instead engage in a practice that would prepare him for this position.

This case is not exceptional. There are a number of cases where improper headstand practice has led to problems such as loss of sensation in the arms, difficulty speaking, etc. Generally, these ailments are the result of positional dependence along with a lack of reflexes. Just as this young student followed his grandfather's advice, students often blindly follow instructions that may not be appropriate for the situation or body. Without self-evaluation and reflection during practice, they cannot connect the problem to its real cause.

A similar misunderstanding can also occur in the case of the practice of pranayama and meditation. Once a man came to us with neck problems. It turns out that he decided to follow the traditional breathing ratio that he found in a book: 1:4:2:1, in which he held his breath for 24 seconds. He chose this ratio based on the assumption that he was holding God within him for 24 seconds during each round of practice, or about 30 minutes a day.

It was obvious that he was straining his system by forcing himself to hold his breath for so long. We recommended a different ratio and his problem was solved. In this case, he inadvertently caused health complications by not having a teacher to observe him and his condition and by assuming that the ratio described in the book would work for everyone.

The student must also understand the real content of what he or she is doing in the practice of yoga. Once a woman came to us and complained that even though she meditated for three hours a day, she had no peace in her mind. It turns out that he uses meditation as an escape from his duties in a large family. True meditation should bring her a sense of calmness that allows her to look at things from a different perspective. Instead, she came out of meditation angry that she had to go back to her daily life again. Meditation is not an escape.

Finally, we would like to caution yoga students to be careful about self-teaching. Learning asana practice by yourself from books is unwise, not because the particular book you are using is lacking in something, but simply because no book can know the details of your condition.

As we have said repeatedly in this book, the guidance of a capable

teacher is essential.

-

Source:

A.G. Mohan: Yoga for Body, Breath and Mind. Boulder: Shambala 1993.

A.G. Mohana a Indry Mohan: https://www.svastha.